The Violin above was made by Giuseppe Guarneri del Jesu in 1741

MATTHEW LAMMERS

Doctoral Lecture Recital in Duncan Recital Hall, Shepherd School of Music, Rice University: "Dialogue with Luthiers - Creating Precision, Progress, and Priorities"

using Keith Hill Violins Opus: 499, 509, 511, 531, 534, 535, 536

Here is a recording of my violin Opus 504 in a Brahms Sonata in G Maj. played by Matthew Lammers for his DMA recital at Rice University. The acoustics of the hall leaves much to be desired I suspect because of the shell intended to improve the acoustics just sequesters the sound coming from the instruments.

Here are recordings of two violins, my Opus 504, and my most recent (finished a week ago) violin, Opus 518, recorded in my violin shop on July 15th, 2019 using a Zoom recorder.

My treatise on The True Art of Making Musical Instruments—A Practical Guide to the Hidden Craft of Enhancing Sound is now published and available on Amazon.com. Here is the link for that page.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1791889611

There has never been a book written that covers the craft of enhancing sound until now. Indeed, most books written about sound are based on the physics of sound. In the 47 years I have been making musical instruments, I have never found it either necessary or useful to know anything about the physics of sound. My reason for this total disregard for such knowledge is that ALL the greatest musical instrument makers from 1400 to 1840 including Stradivari, Guarneri del Jesu, Amati, Ruckers, de Zentis, Blanchet, Taskin, Cristofori, Stein, Hubert, Walther, Graf, Schnitger knew nothing about the physics of sound. That is because all such knowledge wasn’t discovered yet. What these makers knew was vastly more important and valuable, that is, the science and craft of enhancing sound, all knowledge of which, unfortunately, was secreted away only in their instruments.

Now, some people quibble with what I have just written, so in response I would like to have proof where researchers in the area of the physics of sound have figured out how to increase the clarity of the sound of an instrument, increase the immediacy of the sound of a violin, increase the depth of sound, increase the intensity of sound, increase the carrying power of the sound of an instrument, increase the vocal property of a sound, increase the evenness of sound from bass to treble of an instrument, increase the ease of recording quality of an instrument, increase the responsiveness of color flexibility while playing the instrument, increase the ability of the sound to bloom in an instrument, increase the perceptibility of pitch in an instrument, increase the ability of the instrument to reflect the intentions of the player, and last but not least, increase the ability of the sound to capture the listener’s attention. Each of these qualities are what the ancient instrument makers knew how to build into their instruments and it is precisely these qualities that remain beyond the ken of scientists and makers who fancy themselves as acoustical scientists. It is these qualities the knowledge of how to build them into a sound that is secreted away in their instruments. The only scientist I know of who made some progress in tackling these qualities was Jack Fry, but he succeeded by the same approach I myself used for the last 47 years.

My attitude when I began making musical instruments in 1972 was to restrict myself to only that knowledge available to those great musical instrument makers. That body of knowledge, which was acquired over a period of 350 years, had as its foundations the teachings of Pythagoras. Based on his ideas of the musical ratios, makers of all kinds instruments developed the craft of enhancing the sounds of their materials to make their instruments sound as beautiful and as resonant as possible. Then, towards the end of the 18th century, with the development of modern scientific methods and attitudes, all that lovingly acquired ancient Pythagorean based knowledge was put aside and immediately forgotten. Even Conrad Graf in the beginning of the 19th century had to relearn that body of knowledge to produce the sounds of his pianos. But little of what Graf had learned was acquired by apprentices in his workshop. Recovering all that lost knowledge was my goal.

This treatise is meant to preserve this knowledge of how the greatest instrument makers in history thought about sound and how to enhance it. As soon as the book is published I will anounce that here.

Photographs Of My Violins, Viola, And Cello were made by Mickey Dobo Of Nashville

The Violin Shown Below Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 6 2 In 2 0 1 4

A MAJOR BREAKTHROUGH

November 1, 2017

I was told recently by my most rigorous and long-standing critic of my violins, a virtuoso violinist and long time dealer in new and antique violins, "You have achieved what you have been aiming for over the last 40 years in your violin making". What I had told him 10 years ago was that my specific aim was to be able to build violins that were as good in every way conceivable to the best violins made by Stradivari and Guarneri del Jesu.

Such an acknowledgement, for me, had to come from a violinist who was intimately involved in the playing, set up, and sale of the important 18th century Italian violins. He has spent a lifetime dealing in both new and antique violins, playing them, buying and selling them. He knows how the best instruments behave under the bow. I have seen him pick up a violin, put it under his chin, draw one note from the instrument, make a face of disgust and put it down immediately, unwilling to touch it again. He has no interest or patience for inferior sounding and playing violins. Yet he is always looking for passable new instruments to sell in his shop. That is why his approval has been key for me. As well, he always made one or two comments, no more, every time I showed him my instruments, comments that were extremely to the point. And if I addressed myself to those comments and invented means of solving the problem or issue he had pointed out, he would notice the improvement and point out something different that would raise the quality of the next batch of violins. He once told me, with a tone of some surprise, that I was the only violinmaker he knew who could actually accept and then make use of criticism, apparently this behavior is something of a rarity in this field.

When he picked up my most recent violin, one based on Guarneri, finished 2 weeks earlier, he began to play and as he continued to play he exclaimed, "This is a fantastic fiddle!! There isn't anything it can't do. " As he kept playing he said, "It does everything! It’s got everything!" When he finally put the violin down, he picked up a violin made by a violinmaker living in Cremona for whom he said, "This is by a modern maker from Cremona for whom I have a lot of respect. " When he set it down and picked up my violin and played on it again, he stopped and said, "There isn't a single maker today whose violins can come even close to your violins." Naturally, his words were a real acknowledgment and affirmation for me that the path I struck for myself 40 years ago when I began making violins was the right one, the only one I know of that is based entirely on the ears to the virtual exclusion of the eyes.

The violin he was playing is what I call an acoustical copy of an original made by G. Guarneri del Jesu in 1739.

The violin in the recording below was my opus 472 (pictured below), which I retuned as Opus 509, an "acoustical copy" of an original made by G. Guarneri del Jesu in 1739, played by Maggie Kasinger. This is the first recording I have to post that reflects my breakthrough herein described.

Violin by Keith Hill opus 472 / 509 retuned in January 2018

Credit for the success of my 40 year long undertaking is enthusiastically shared with: my critic who chooses to remain anonymous, who kindly took me at my word when I invited him to spare nothing in offering negative criticism, I say this because that is the only criticism from which improvements can be realized. I told him that this success would not have happened without him. With: Matt Lammers, my research assistant, who has been intimately involved in my violin making since 2015 when he made recordings on 11 different violins so I could post them on my website. Matt's ability to understand what I am doing and the practical and theoretical underpinnings of my violin making has led to half a dozen or so discoveries on my part relating to technical means of solving problems in my violins. His dogged determination to see me to my goal has been an inspiration. Without Matt's ability to identify specific minor problems that only an articulate artistic musician with a fine mechanical sense, cultivated taste, and interest in the violin as an expressive tool might notice, this work would never come to fruition as rapidly as it has as in the last 2 years. With: Marianne Ploger, whose discoveries back in the early 80's of the last century of 'frequency associated timbre' and whose insights over the last 33 years of our marriage have contributed to my understanding of how the ancient violin makers were thinking about sound, especially in the last 7 weeks when my one nagging question that has kept me searching for the answer over the last 8 years, that of how the ancient makers made decisions about how to optimize the sound of each piece of wood, was finally answered. With: Christine Arveil, who opened my eyes to the seemingly infinite subtlety in the application of my varnish and taught me the appropriate techniques to enhance the artistic aspect of my violins. With: Artiom Sinelnikov, my first violin making acoustical technology student and then my research partner, who has since become an outstanding acoustical scientist in his own right and who has made acoustical discoveries over the last eight years that added to our store of knowledge thus bringing the level of acoustical quality in our violins to an even higher level of quality acoustically and practically. With: Ladislav Prokop, also my research partner and my second violin making acoustical technology student, whose expertise in setting up violins made possible his appointment as top set up specialist at a violin house in London where the administration of that business blessed our collaboration in making violin acoustical observations of the best violins in the house. With: Devin Golka, my harpsichord making assistant, whose cheerful help moved ideas from the theoretical to the practical with aplomb. And not least with: Shigetoshi Yamada whose assistance in selling my violins and faith in my ability to reach my goal helped my work by making sure that each violin was setup to a professional's standard then finding the violinists who bought my violins; thus was the work financed these 40 years. And finally, with all those violinmakers whose scoffing ridicule regarding my approach only strengthened my resolve to avoid their errors of thinking and habits of making musical instruments with the eyes instead of the ears. From my experience, it is their behavior of focusing on the "box" as the true source of knowledge about the violin that has, alas, been their greatest barrier to understanding the sound of the violin. Its not about the box, its about the sound. The business of making a sound with dozens of specific acoustical traits, properties, and characteristics is what causes the box to assume its precise appearance in every detail and dimension.

I plan to have Matt Lammers make another batch of recordings as soon as possible on as many violins incorporating this new acoustical technology so everyone can hear the differences between the newest violins and the violins I was making back in 2015 and the similarities and differences between the newest violins I will be making in 2017-18 to be compared with the recordings of the antique violins already on my website.

Now all I want to do is make as many violins of this caliber, or better, as possible for the rest of my life.

Here, just below, are all of the recordings made in 2015 on what were then my new instruments listed by opus number. And, as you scroll down past the following text you will come to the various recordings of antiques compared to the sounds of these violins along with photos of each of my instruments. Now that I have achieved a new much higher standard of quality in the sound of my violins, I plan to remake recordings of all the same pieces in order to again compare my results directly with the recorded sounds of the antique violins. I will post that new set of recordings as soon as they are ready. When that will be I can not say.

Most of these recordings were made for me by violinist, Matthew Lammers, a recent graduate of the Blair School of Music, who is currently aiming for a Masters degree in Violin at Rice University. Only two of the group of recordings, the Paganini Cantabile in D maj. and the Brahms Hungarian Dance No. 17, were performed by Mary Grace Johnson and Nathan Lowry respectively. They along with Daniel Moore, viola, and Alex Krew, cello, are students at the Blair School of Music, Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Jennifer McGuire, who did all the piano accompaniments, made it possible to realize the musical result I was looking for in making my recordings. Her intelligence, wit, and competence as a musician and communicator allowed the sound of the violins and the affects in the music making to shine free.

All the commercially recorded pieces using the great antique Cremonese violins, chosen for the purposes of making comparisons with my violins, were played by Riggerio Ricci, Xue Wei, or Salvatore Accardo. Different recording engineers, each with varying tastes regarding microphone placement, type of microphone, and volume settings for these recordings means that you will have to empirically establish the proper volume level for each track by attending to the volume of the piano. However, those volume levels may also have been engineered in the recording studio to favor the violin.

SOME "PARALLEL" RECORDINGS

So Listeners Can Compare The Different Sounds Of My Earlier Violins

With The Sounds Of Some Of The Best Antique Cremonese Violins That Exist

by Keith Hill © 2017

The Violin used in the above recording that is Pictured Below was made by Keith Hill and Artiom Sinelnikov #3 in 2014

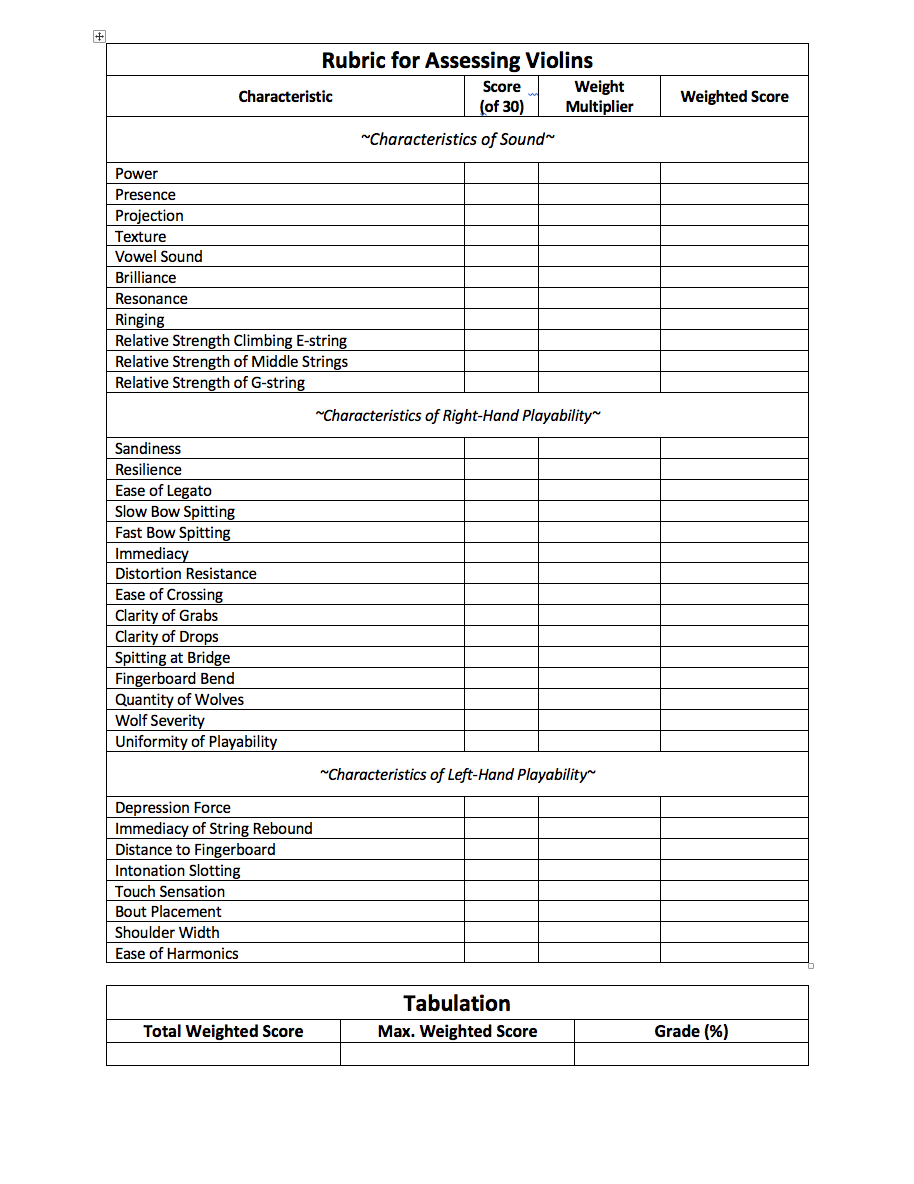

39 Traits and Properties of Great Sounding Violins

by Keith Hill © 2015

1. Carrying Power - to completely fill a very large hall

2. Projection of tone - the sound goes out to the listener;

listeners are not required to strain to hear the violin even at a great distance

3. Great Volume - to play concertos with a large ensemble

4. Ease of Response - ready to sound at the will of the player at all levels and touches

5. Balance of sound across the strings

6. Directness of sound - creates the feeling of immediacy in the sound

7. Evenness of sound up and down the fingerboard

8. Depth of tone - to create the effect of Paradox

9. Intense Resonance - to fully support the softest sound produced

10. Clarity of tone - to be easily heard in a complex texture

11. Penetration of tone over large distances without loss of quality

12. Breadth of tone - to surround the ears of each listener

13. Flexibility of response -reflects the bow's slightest motion

14. Subtlety of tone - mirrors the soul of the player

15. Brilliance - to excite or stir the player and listener

16. Color - conveys every timbre and affect intended by the player

17. Tonal Reserve - a sound that keeps on giving, never caving in or reaching a ceiling

18. Strong Sensation of Pitch - makes playing in-tune easy

19. Ringing tone - gives the effect that the instrument is singing

20. Intensity of tone - creates a feeling that the instrument is alive

21. Sweetness of tone - to gratify the player as well as the listener

22. Focused or Centered tone - creates a solid core to the sound

23. Buoyancy of tone - a lightness of effect...the sound floats

24. Velvetiness - the effect that the sound is integrated and smoothly blended

25. Resiliency of tone - sound appears to bounce, when needed

26. Stability of tone - the tone/pitch holds steady on long slow bow strokes

27. Personality - the voice of the instrument feels human

28. Fullness of tone - the ears and mind are filled with the sound

29. Strength of timbre - the sound color is clear and powerful

30. Ease of producing harmonics

31. Each note begins with a Cercare dela Nota (pronounced: chair-car-eeh - a 17th century Italian technique in which a lower note rises suddenly and silently to a main note)

32. Overglow-the effect of the sound continuing to sound into the next note creating a seamless gesture of notes...otherwise known as legato in music...technically speaking the effect of overglow is also called elision as one tone elides to another in a very connected manner.

33. Distortion Resistance - strings resist being distorted

34. Powerful Upper Register - imitating the high notes of a singer

35. Ease of making a good sound when bowing Close to the Bridge

36. Able to generate full resonance even using a very slow, soft bowing stroke

37. Tonal flexibility imitating the expressiveness of the speaking human voice

38. According to violinist, Ole Bull, "the violins of Gasparo da Salo and Guarneri have the sound of a trumpet, horn or flute; the violins of Stradivari have the sound of an oboe and clarinet; and those of the Amati family, of the English Horn and the Human voice"

39. The sensation when bowing is smooth like touching silk

The violin in the above recording was made by Keith Hill Opus 462 in 2014

The Violin used in the above recording that is pictured here below was made by Keith Hill Opus 425 made in 2009 and acoustically upgraded in 2014

This Violin Heard In The Above Recording Is Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 6 0 In 2 0 1 4

This Violin Heard In The Above Recording Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 6 7 In 2 0 14

This Violin Heard In The Above Recording Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 6 1 In 2 0 14

This Violin Heard In The Recording Above Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 6 8 In 2 0 1 5

This Violin Below Heard In The Above Recording Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 7 1 In 2 0 1 5

The Violin Pictured Below Heard In The Second To Last Recording Above Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 6 6 In 2 0 1 5

This Violin Below Heard In The Last Recording Above Was Made By Keith Hill Opus 4 7 2 In 2 0 1 5

What follows are recordings of the 1st movement from the Beethoven String Quartet in G major Opus 18 No. 2 1. Allegro. To compare the sounds of of my instruments with others that are antiques (though of unknown origin) I have supplied tracks from two different professional Quartets that I knew used all antique Italian instruments, the Végh Quartet and the Guarneri Quartet followed by the same movement using my instruments.

Photos of the Hill String Quartet are shown below the audio samples.

What follows are recordings of the 4th movement from the Beethoven String Quartet in G major Opus 18 No. 2 the Allegro Qolto Quasi Presto. To compare the sounds of of my instruments with others that are antiques (though of unknown origin) I have supplied tracks from two different famous professional Quartets, the Guarneri Quartet and the Végh Quartet followed by the same movements using my instruments. Photos of the Hill String Quartet are shown below the audio samples.

Violin opus 4 6 8 is th e first violin in the quartet

Violin Opus 4 2 5 is the second violin in the quartet

The Viola Opus 4 6 4 in the quartet - it is a 16" viola

Pictured here is the K e i t h H i l l cello opus 4 6 5 in the quartet

Violin below used in the above recording was made by Keith Hill and Artiom Sinelnikov #1 in 2014

Violin used in the preceding recording was made by Keith Hill Opus 469 a small pattern violin in 2015

The violin heard in the recording above was made by Keith Hill and Artiom Sinelnikov #2 in 2014

About Matthew Lammers

Violinist Matt Lammers is a 2015 Magna Cum Laude graduate of the Blair School of Music (Vanderbilt University) from the studios of Christian Teal and Carolyn Huebl, and he has begun his graduate studies with Paul Kantor at the Shepherd School of Music (Rice University). A native of Eden Prairie, MN, he studied with Ray Shows of the Artaria String Quartet as well. As a chamber musician he is a prizewinner at the St. Paul String Quartet, MTNA, and Ravinia’s Discover®, and Fischoff national chamber music competitions and has performed in concert joining members of the Nashville Symphony and Blair School faculty. His performance on National Public Radio’s From the Top with the Malik Quartet is rebroadcast regularly, and his recording of the Barber Concerto for MN Public Radio has also been broadcast on a number of occasions.

As an orchestral musician he is a substitute with the MN Orchestra, has served as concertmaster of the Vanderbilt Orchestra and BLAIR Ensemble, and attended the Aspen Music Festival and Brevard Music Center to study with Paul Kantor and William Preucil respectively.

He was named winner of the 2014 Jean Keller Heard Prize for string performance, the inaugural Christian Teal Award for collaborative innovation in 2015, and the 2015 Michael Rabin Prize for excellence in musical performance following his performance of the Beethoven Concerto with the BLAIR Ensemble and world premier of Jack Coen’s Hyperthymesia (for violin and electronics).

A committed pedagogue, he has served on the faculty of the W.O. Smith Community Music School (Nashville) and as a counselor/coach at the Stringwood Chamber Music Institute. He also believes that exposing those who wouldn’t normally experience classical music to it in approachable, informal settings is vital to the longevity and growth of the art form and has founded and directed a number of chamber music series’ that take place in unlikely venues across Nashville.

VIDEOS OF ANTIQUE VIOLINS

These Video Addresses Below Feature The Sounds Of Excellent 18th Century Mostly Italian Violins, Violas, And Cellos By Important Cremonese Violin Makers

As these videos are all embeded from the internet, a note of gratitude must be made to the performers and to YouTube