ABOUT KEITH HILL - LUTHIER

List of Contents

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

PEOPLE WHO HAVE INFLUENCED ME AND MY WORK

REVIEWS OF THE WORK AND IDEAS OF KEITH HILL

INTERVIEW WITH KEITH HILL - by Matthew James Redsell - in 1987

INTERVIEW WITH KEITH HILL - by Elatia Harris

OPUS NUMBER LIST of Harpsichords, Lautenwerks, Fortepianos, Clavichords and Violins

OUTPUT OF KEITH HILL - LUTHIER Instruments with Opus Numbers as of February 8 2024

My treatise on The True Art of Making Musical Instruments—A Practical Guide to the Hidden Craft of Enhancing Sound is now published and available on Amazon.com. Here is the link for that page.

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1791889611

There has never been a book written that covers the craft of enhancing sound until now. Indeed, most books written about sound are based on the physics of sound. In the 56 years I have been making musical instruments, I have never once found it either necessary or useful to know anything about the physics of sound. My reason for this total disregard for such knowledge is that ALL the greatest musical instrument makers from 1400 to 1840 including Stradivari, Guarneri del Jesu, Amati, Ruckers, de Zentis, Blanchet, Taskin, Cristofori, Stein, Hubert, Walther, Graf, Schnitger knew nothing about the physics of sound, what we today consider important to know. That is because all such knowledge wasn’t discovered yet. The Physics of Acoustics from its beginning was an EYE / VISION based science, and still is. That is why it is irrelevant for the purposes of enhancing the sound of a musical instrument. What these great musical instrument makers knew was vastly more important and valuable, that is, the science and craft of enhancing sound, all knowledge of which, unfortunately, was secreted away only in their instruments. Theirs was an EAR / HEARING based science…make no mistake, it is a science in the strictest sense. It is capable of being taught, learned and practiced to the level of great art. But its results are not comprehensible to an EYE based scientific mentality, a truth that is evidenced by a total failure, over the last 250 years, to understand how such great sounding instruments are produced.

Now, some people quibble with what I have just written. In response, I would like to have proof where researchers in the area of the physics of sound have figured out how to increase the clarity of the sound of an instrument, increase the immediacy of the sound of a violin, increase the depth of sound, increase the intensity of sound, increase the carrying power of the sound of an instrument, increase the vocal property of a sound, increase the evenness of sound from bass to treble of an instrument, increase the ease of recording quality of an instrument, increase the responsiveness of color flexibility while playing the instrument, increase the ability of the sound to bloom in an instrument, increase the perceptibility of pitch in an instrument, increase the ability of the instrument to reflect the intentions of the player, and last but not least, increase the ability of the sound to capture the listener’s attention. Each of these qualities are what the ancient instrument makers knew how to build into their instruments and it is precisely these qualities that remain beyond the ken of scientists and makers who fancy themselves as acoustical scientists. It is these qualities the knowledge of how to build them into a sound that is secreted away in their instruments. The only scientist I know of who made some progress in tackling these qualities was Jack Fry, but he succeeded by the same approach I myself used for the last 56 years.

My attitude when I began making musical instruments in 1972 was to restrict myself to only that knowledge available to those great musical instrument makers. That body of knowledge, which was acquired over a period of 350 years, had as its foundations the teachings of Pythagoras. Based on his ideas of the musical ratios, makers of all kinds instruments developed the craft of enhancing the sounds of their materials to make their instruments sound as beautiful and as resonant as possible. Then, towards the end of the 18th century, with the development of modern scientific methods and attitudes, all that lovingly acquired ancient Pythagorean based knowledge was put aside and immediately forgotten. Even Conrad Graf in the beginning of the 19th century had to relearn that body of knowledge to produce the sounds of his pianos. But little of what Graf had learned was acquired by apprentices in his workshop. Recovering all that lost knowledge was my goal.

This treatise is meant to preserve this knowledge of how the greatest instrument makers in history thought about sound and how to enhance it. In writing this treatise, it was my aim to set forth the principles underlying the mechanics of enhancing sound. It was not meant to provide formulas, technical directions, or recipes. Each person equipped with these principles should be able to make sense of them by following a simple Cause and Effect approach.

What follows is a review one reader posted on the webpage for the Treatise…

“Here is my review of this treatise, to speak colloquially, WOW!! Although I continue to browse, in bits and pieces via an admittedly somewhat random roaming of various topics, I have already been blown away by the treatise -- much in the same way as the effects on me of those harpsichords / violins /violas da gamba and a double bass by Keith Hill which I've been privileged to hear.

From the standpoints of content, organization and clarity of expression, the book is a masterpiece. The visuals are also terrific. Like so many of Mr. Hill’s instruments, the treatise will assuredly stand as his legacy into the indefinite future ("indefinite" because I am not sure how much longer humankind will exist on this earth . . .).

Frankly, I did not expect the treatise to be SO easy to read and absorb. In that respect, I have in fact been positively startled. The writing in the treatise is totally direct. Its approach comes across as no-nonsense, objective, fair and -- just as important -- the voice of someone generously urging seekers to find their better selves. Hill is a fabulous coach.

I can only hope that serious instrument builders worldwide learn of, and embrace, the teachings in this treatise. For those of us who just "like to know how things work", it is a treasure house. I look forward to spending many instructive hours with this work.

JR

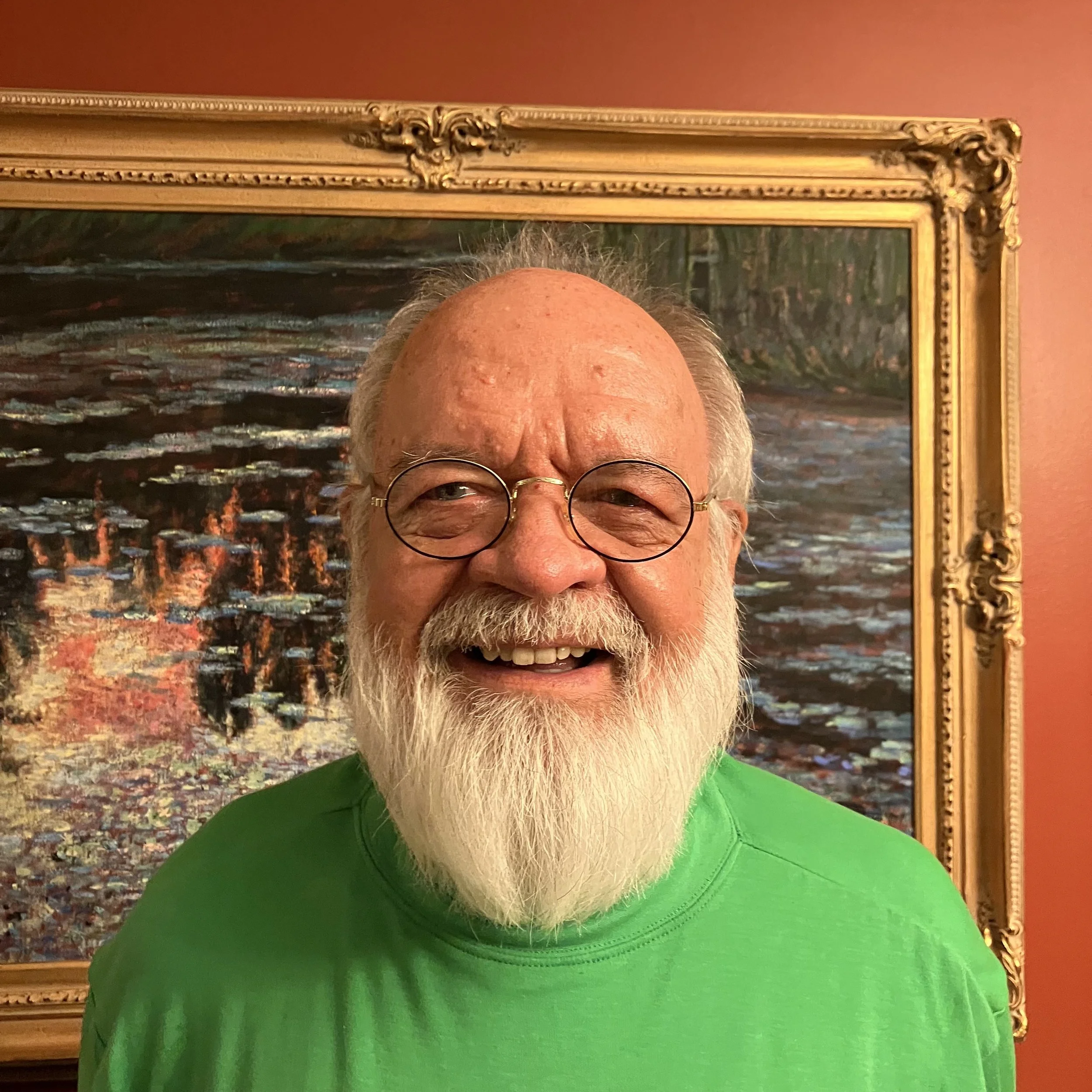

Keith Hill - luthier at age 77

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

- Specialist in Acoustics as practiced in the 17th and 18th centuries.

- Aesthetic Scientist involved in researches on cognition, perception, and brain function to establish the underlying principles behind musical and visual artistic endeavors of centuries previous to the 20th century.

- Materials Scientist with emphasis on the acoustical properties of materials

- Metaphysical philosopher-interested in explaining the behavior and nature of the Soul from a non-religious point of view.

- Specialist in Musical Communication training.

- Artist: Painter - in the Modern Impressionist style with a special interest in understanding the modes of perception of the great painters of the past.

- Artist and historian specializing in the decorative techniques used in Europe from 1600 - 1800. With a special interest in understanding the influence of methods and attitudes on the results.

- Musician (harpsichordist), with a special interest in improvisation and improvisation pedagogy

- Maker of more than 320 keyboard instruments (harpsichords, clavichords, and fortepianos) and 130 bowed stringed instruments (violins, violas da Gamba, etc.) Some of these instrument do not appear in the Opus numbers due to their highly experimental nature. See lists below of instruments made.

- Clinician doing workshops on the Craft of Musical Communication at conservatories in US and in Europe (Oberlin Conservatory, Royal Danish Conservatory in Copenhagen, Bruchner Conservatory, Linz, Hochschule für Musik in Bremen, Göteborg University, Hochschule für Kunst und Musik- Berlin, Hochschule für Musik-Freiburg, University of Wisconsin/Stevens Point Department of Music, etc.

- Exhibited paintings at the Stove Factory Gallery in Charlestown, MA and the Chelsea Gallery in Chelsea, MI

- Decorated soundboards and cases of more than 150 of his own instruments

- Presenter at the Symposium on Improvisation at Eastern Michigan University.

- Author of numerous articles on musical, aesthetic, and instrument making subjects.

- Alchemist-specializing in research in acoustical varnishes and leathers

- Author of a Treatise on the True Art of Making Musical Instruments - a 250 page volume on the principles of acoustics made practical for instrument makers as well as essays discussing how those principles may be successfully applied.

- Teacher of Harpsichord, Improvisation, and Musical Communication

- Artistic mentor to various composers and performers

EDUCATION

1971-1972

- Graduate studies in Harpsichord with Anneke Uittenbosch at the Sweelinck Conservatorium, Amsterdam, Netherlands

1971

- Bachelor of Music in Music History at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI

1966-1971

- Undergraduate Music studies with Wendell Westcott (piano) and Corliss Arnold (organ) at Michigan State University

1969-1970

- Special course work in Historical temperaments and tunings and piano technology with Owen Jorgensen at Michigan State University.

1972 - 2002

- Organological Research studies on harpsichord and fortepiano making practices and acoustics conducted on the collections at the Gemeentemuseum, Den Haag, the Germanisches National Museum in Nüremberg, the Russell Collection at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland, the collection of musical instruments in the Fine Arts Museum in Brussels, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, in 1972 the Skinner Collection at Yale University, New Haven, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Smithsonian, Washington, DC, in 1978, the Paris Conservatoire, the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien, and the Stadt Museum Berlin in 1996, and the Claudius Collection in Copenhagen in 2002.

- Began musical instrument making professionally in Grand Rapids, MI in 1972

- Developed the concept that Quality resulted exclusively from correctly applied Universal Principles-subsequently articulated 33 Universal Principles which govern human perception of quality in 1977

- Began research in violin acoustics in 1978

- Co-founder of the Institute for Musical Perception (1999) Ann Arbor, MI

- Teacher of Musical Communication since 1997

PRESENT

COMPARING THE

STANDARD MODEL OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE TO BACH’S CANTABILE STYLE OF PLAYING

By Keith Hill and Marianne Ploger Nashville, TN 2025

The Standard Model in Music Performance

The Standard Model in Music is founded on a set of performance requirements used to determine a musician’s level of professionalism. Those are as follows:

Technical Requirements

1. Metrical precision and accuracy as determined from the printed score.

2. Notational precision and accuracy as determined from the printed score.

3. Precision and accuracy of vertical and linear tonal alignment as determined from the appearance of the printed score.

4. Realization of expression limited to that indicated on the printed score.

5. Expressive devices limited to Articulation, Gradual or abrupt changes in volume, speed, texture, timbre, etc., as indicated on the printed score.

6. Stylistic interpretive devices based on traditional practices such as: vibrato, tempo, volume, and instrumentation as maybe determined from the printed score.

7. In-tune based on equal temperament at A – 440 + or –

8. Scores that do not indicate how the notes are to be performed are played legato.

9. No particular rhythmic hierarchy: absence of strong and weak beats in a bar.

Aesthetic Requirements

1. Correct performance results from adherence to that which appears on the printed score.

2. Take no liberties with the printed score.

3. Treat the printed score as the final arbiter of the composer’s intentions

4. Produce the best sound possible.

The Standard Model with Historically Informed Musical Performance Practice

Apply all the Standard Model Aesthetic Requirements listed above, then add all the following Historically Informed Musical Performance Practices currently understood as musicologically authentic :

1. Correct Instrumentation based on Historically Informed building practices.

2. Correct Pitch standard based on HIMPP

3. Correct Tuning or Temperament based on HIMPP

4. Correct technique based on specific historical sources, especially rhythmic hierarchy.

5. Correct technique based on instrument, national and historical construction style.

6. Correct articulations based on composer, national style, and historical style.

7. Correct ornamentation based on composer, national style, and historical style.

8. Correct style based on HIMPP under the Standard Model.

9. Absence of Vibrato except for soloists/singers.

10. Using faster tempi.

11. When in doubt about performance style play in a detached manner

Problems inherent in the Standard Model in Music Performance

The problems built into the Standard Model in Music from the outset arose from various technical and cultural developments all of which formed a kind of unspoken consensus classically trained musicians.

One: The establishment of schools of music, conservatories, and music departments in colleges and universities led to the practice of certifying and conferring degrees on matriculating students. Certification required standards of professionalism that were considered objective. This process of certifying students required the institutions themselves to be certified regarding the content and competency of the information being taught. It eventually became necessary to have a set of standards that could be employed to objectively evaluate the professional achievement of each student. A student who successfully fulfilled the requirements of the standard model was then certified and earned a degree.

Two: Over time, technical advances in film, phonography, and printing exerted an influence on the need for increasing precision and accuracy in musical performances. The technical developments in sound recording meant that the performers/musicians had to be more rigorously prepared to meet the demands of the recording industry. In many ways, it was the attitude of recording engineers and editors that determined who was considered professional and who was not competent enough to have a career as a performing musician. So the curricula of the conservatories and schools of music conformed to the more stringent requirements being demanded by the recording engineers and editors. With each improvement in sound recording technology raised the standards of the model. Eventually, the technical crafts became incorporated directly into the conservatories and schools of music. Standards of perfection increased to keep pace with the recording industry.

Three: As music engraving gradually became responsive to developments in musicology, music scores became cleaner. Editorial suggestions common in the late 19th century and early 20th century editions of printed music, intended to help performers interpret the music, disappeared. With the onset of the URTEXT movement in musicology, scores labeled Urtext became sterilized of all but the notes of the original manuscripts and the layout of these scores took on a mathematical and mechanical rigor. Performers consequently mirrored the Urtext mentality and assumed the mathematical, mechanical rigor suggested by the printed scores. The musicological aesthetic became: “Let the music speak for itself.”

Fourth: Consequently, “Let the Music Speak for itself” justified the “One ought not take liberties with the score” philosophy that propped up the Standard Model.

Fifth: To force the change in performance practices, in order to cement the Standard Model, phrases of derision were aimed at musicians who complained about making the change. Example: “Eliminate the sloppy sentimentalisms of a bygone era!” Such phrases are a common academic tactic to force compliance to a meaningless rule designed to bully and belittle voices of disagreement. The Standard Model was a tactic of a fascist dictatorship intended to overthrow the Cantabile Style of playing music.

Interestingly, Arnold Schoenberg, whose theories of atonalism paved the way for the standard model to become entrenched in classical music training, actually wrote an article in 1948 titled: Today’s Manner of Playing Classical Music. In this article, Schoenberg complained about the erasure of expressive playing happening everywhere, especially in Europe where there had existed an established culture of expressive playing in music. Arnold blamed American Rock music as the cause.

Questioning the Standard Model

When any reasonable musician examines the list of requirements to establish a level of professional competence, every requirement seems reasonable and valuable. Were one to question that set of requirements and understand the underlying errors in thinking behind each requirement, they would fail the test of scrutiny. Begin with the first: Metrical precision and accuracy as determined from the printed score.

What about Affect?

In music, throughout the history of music with the exception of the last 90 years, the overarching aim or outcome of playing music has been the concept of Affekt. Affect, or Affekt (from the German), is not the self-expressive emotional nonsense used by purveyors of the Standard Model. Affect is actually a language of suggestion of human attitudes, states of mind, emotions, and physical behaviors employing the elements of melody, rhythm, and harmony. Again, affect is a language of suggestion, not expression. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the term used for this language in German was Affektenlehre (Doctrine of Affects) This Doctrine was less important to a practicing musician than understanding how to employ the elements needed to create music that was highly suggestive of some human feeling. Here is the problem! Every sound conveys affect. It doesn’t matter if the feeling being suggested is intentional or not, every sound conveys affect.

What is Affect Content?

Let’s ask the question, what is the affect “content” of metrical precision and accuracy as determined from the printed score? Metrical precision is characterized as being metronomic, military, mind numbing, boring, scolding, deadly, mechanical, cold, calculating, indifferent, fear, anger, etc. It makes no affective difference to anything else that might be going on musically. If metrical precision is present, those affects will be the overarching feelings being suggested. Even if the composer has been intending to suggest a completely opposite affect like sweetness and tenderness, if the performer seeing a series of perfectly regular and equal note values on the printed page and performs the music in a manner that is metrically precise, the affect will be suggesting coldness and mechanical indifference. The stylistic function of the standard model is to ensure a performance that is clean and objective. The side effect of adopting the highly mannered style of the standard model is to guarantee that every performance of the music will sound exactly like the previous 983 performances.

What got tossed out? The baby or the bathwater?

In the 1940’s, the Standard Model became firmly established as the modus operandi both in Europe and in America. At the time it was heralded as a new, cleaner, more objective style of playing music. This style was designed specifically to brush away the remnants of the previous sloppy sentimental romantic style that had dominated musical performances. That so-called sloppy sentimental romantic style of playing had been developing and evolving over the previous centuries since 1400! Every so-called rational attempt to sterilizes the world of dirt ends in killing the baby.

What is the purpose of the Standard Model?

An even more insidious side effect of adopting the Standard Model manner is considerably less well understood. That is, in a sonic environment such as a perfectly metrical performance of music, errors stick out like a proverbial sore thumb. Even worse, errors actually become the only meaning available. This is well understood by seasoned professional musicians, which is why they enforce that requirement so rigorously. Young professionals learn quickly to avoid making mistakes. Many, however, discover only after 12 years of higher level training in music that the fear of making mistakes compounds over time and leads to performance anxiety. What teachers and students fail to realize is that perfectly metrical playing is mind-numbingly boring, especially in the midst of performing. Mistakes happen when the mind of a performer is bored. It is a feedback loop that guarantees the manufacture of errors. The only students who can play note perfectly in the presence of a brain that is fast asleep are the truly talented students. But still the standard model is paramount.

Who is truly happy about all this?

Having spent a lifetime career in music, 1966 to 2025, observing musicians closely, it is evident to us that Standard Model performers are frustrated and disillusioned. What begins in youth as a passionate love of music shrivels to resignation under the heel of the Standard Model, and eventually morphs into careers that don’t involve playing music for others to enjoy.

Bach’s Cantabile Style of Playing

In the Preface of the Inventions and Sinfonias Bach specifies the pre-eminence of cantabile playing. It reads: "Honest method, by which the amateurs of the keyboard – especially, however, those desirous of learning – are shown a clear way not only (1) to learn to play cleanly in two parts, but also, after further progress, (2) to handle three obligate parts correctly and well; and along with this not only to obtain good inventions (ideas) but to develop the same well; above all, however, to achieve a cantabile style in playing and at the same time acquire a strong foretaste of composition."

The Bach Reader includes several references to that emphasis Bach placed on independence of voices in performance: "Bach was the most daring in this respect, and therefore his things require a quite special style of performance, exactly suited to his manner of writing, for otherwise many of his things can hardly be listened to. Anyone who does not have a complete knowledge of harmony must not make bold to play his difficult things; but if one finds the right style of performance for them, even his most learned fugues sound beautiful." (from Kirnberger in 1774) p.261

And: "He invented the convenient and sure fingering and the significant style of performance, with which he cleverly conbined the ornamental manner of the French artists of the time, and thus made the perfecting of the clavier important and necessary, in which task Silbermann was so fortunately at his side." (Reichardt 1796) p.265

It was only when a letter by Friedrich Griepenkerl from 12 April, 1842 was published did we discover exactly what that "right style of performance, that special style of performance, that signifiant style of performance" actually was. Interestingly, the same was being said of Chopin's manner of playing. People who mentioned his distinctive manner of playing never said what that involved.

The famous letter from Friedrich Griepenkerl written on 12 April 1842.

The great grand student of JS Bach, Friedrich Griepenkerl, wrote in a letter when he was very old: "Bach himself, his sons, and Forkel played the masterpieces with such a profound declamation that they sounded like polyphonic songs sung by individual great artist singers. Thereby, all means of good singing were brought into use. No Cercare, no Portamento was missing, even breathing was in all the right places...Bach's music wants to be sung with the maximum of art." Andreas Arand in Ars Organi . 49.Jhg . März 2001, p.12.

The definition of the words Cercare and Portamento appear in separate dictionaries of Music. Riemann’s 19th cent. Dictionary defines Cercare and Cercare dela Nota as “a 17th century Italian ornament in which the lower or upper auxiliary note sound rapidly and silently to the main note.”

Portamento is defined in a 17th century Italian dictionary as: “the manner of managing tones on the organ.”

Some interesting connections: Griepenkerl was a student of Nicolas Forkel. Forkel was a student of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, who was a student and son of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Sarah Levy, Mendelssohn’s aunt, studied with both Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and Carl Philip Emanuel Bach and commissioned the double concerto for Harpsichord and Fortepiano from CPE Bach. Mendelssohn’s grand mother Bella gave him the score to the St. Matthew Passion of Bach. JS Bach himself taught Kirnberger who taught Fasch who taught Zelter who taught both Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn. https://youtu.be/QW6clGWyiDE?si=I5orIEuk-B_naEj3

The Cardinal signs for a Cantabile Style when Playing Music

1. “Endeavor to avoid everything mechanical and slavish. Play from the Soul, not like a trained bird.” From the Versuch by CPE Bach.

2. “Maintain strict time” also from the Versuch by CPE Bach, was instantly adopted into the Standard Model due to a gross false interpretation of the word TIME by 20th century musicologists. 18th Century time was not the same as modern notions of time as measured by an atomic clock. You cannot interpret time as meter in the metronomical sense…the mistake that most music teachers make. Remember, “Endeavor to avoid everything mechanical and slavish!” Therefore the more sensible understanding of strict time must refer to time as in flow of time. In this sense, yes, it is essential to maintain strict flow, strict flow, that is, of musical thought in performance. There is no such thing as flow in a Standard Model performance…maintaining strict meter is fake flow. The key is: Flow of Musical Thought. Curiously, it is perfectly possible to interrupt entirely both sound and meter for a considerable duration and still maintain the flow of musical thought.

3. True Independence of voices in performance of music. Every tone at every volume on every different pitch level is unique in timbre and in tendency. Musical intelligence makes clear the meaning of each tone according to the references it suggests. This is also the underlying logic behind syntax or grammar in language. Tonal music based on the Ionian mode behaves exactly like grammar in language. All parts of the tonal scale refer to the tonic just as all parts of speech refer to the subject in a sentence.

4. No Cercare dela nota is missing. This stems from the human utterance signaling recognition and agreement or the ability to follow a thought. Normal human speech is replete with the cercare. Everyone uses this mode of utterance so often that it is totally unrecognized for what it is. Computer speech cannot reproduce this utterance which is why that monotonous variety of verbal output is summarily rejected by people.

5. No Portamento is missing. Portamento is any means of managing tones in music that increases the efficiency of musical communication. There are 11 specific technical devices derived from human speech that transmit meaning and attitude from one mind to that of another.

6. Vacillare. Tosi in his Art of the Florid Song (1736) states: “The singer should endeavor to sing before the beat or after the beat and never with the beat.”

7. Dyssynchrony of tones in performance. Avoid strict alignment of tones in a vertical sense unless you mean it.

8. Endeavor to create gestures as often as possible. Gestures made of sound are more easily followed and remembered because the normal human brain easily perceives sound that is loaded with meaning. The more directional and shaped those sounds are generated, the clearer the meaning is both received and understood.

9. Legato is the technical means of connecting tones in the mind’s ear. The range of touch that conveys to the mind’s ear is only limited by the skill of the performer.

10. Tempo. Speed of movement suggests health or disease in terms of musical character and quality. Andante suggests the normal speed of a person aiming to be someplace specific…that speed is expressed as 116 MM. 116MM also indicates the normal flow of accents in human speech. The Golden Mean:: (1:1.618) of 116MM is 72MM and this tempo appears to govern the moments of change in human conversation, pauses, and points of emphasis being expressed.

Footnote:

How the Students of Liszt played, with critical comments by Sebastien Dupuis dismissing their playing

https://youtu.be/qKCL4Mh7Ci4?si=gK-yQzgVROC4wvbq

My comments about this youtuber’s comments

It is extremely clear to me that this pianist understands nothing about musical communication. Every standard that he listed in the first minutes of this video were adopted after 1940. From that moment it is precisely those standards of hands together, perfection of meter, perfection of performance, note error requirements, were all the beginning of the drift of the audience away from the concert halls especially from solo piano concerts. The sales of recordings of classical music from that moment to 1978 went from 73% of all recording sold in Europe and the US to 3% of all recordings sold in Europe and the US. Now hardly anyone can produce an audience for a solo piano concert compared to 1906. These pianists studied with Liszt to learn how to communicate music so that a normal music lover would want to attend a solo piano concert. What he is clearly ignorant of are the techniques that they were learning. These techniques are all derived from human perception, cognition and communication. When these techniques are eliminated by the use of the performance standards he supports by his mouth in this video, the only listeners who want to hear such performances are so-called left brain dominant individuals, otherwise known as bean counters. The modern performance standards were adopted because it was too hard for juries of judges of competitions to agree about what was an error in performance...so they removed entirely all variances from the printed page.

CHECKLIST FOR EVALUATING PLAYABILITY iN VIOLINS

Ongoing research in the area of

Playability in violin making with Matthew S. Lammers DMA,

Co-Founder and Co-Director, Opus 1 Chamber Music School

Lecturer of Violin and Chamber Music, Shepherd School of Music, Rice University

Violinist, The Axiom Quartet.

BEHAVIORS AND PERCEPTUAL SOUND QUALITIES IN VIOLINS, VIOLAS, AND CELLOS

by Keith Hill and Matthew Lammers © 2016 Nashville

with, Gennady & Yevgeny Chepovetsky

(www.yevgenychepovetsky.com) (https://youtu.be/C41flbm2c64)

Gradient scales

0 is always bad, negative, poor, flaccid, weak - 10 is always good, positive, excellent, intense, strong

MATTERS OF PLAYABILITY

LH = Left Hand - RH = Right Hand

Manageability of Play - RH

Skating = 0 versus Hugging = 10

Skating feels like slipping on a banana peel - Hugging feels like a magnetic attraction

Ease of Articulation - RH

Troublesome = 0 versus Easy = 10

Ease of Response - ready to sound at the will of the player

Tonal Balance

Poor = 0 versus Well balanced = 10

Balance of sound across the strings

Evenness of Sound

Uneven = 0 versus Easily Even = 10

Evenness of sound up and down the fingerboard

Uniformity Across Strings of LH Resistance

Uneven resistance = 0 versus Evenness of Resistance = 10

Tracking- RH

Wandering = 0 versus Tracking = 10

Wandering feels like the bow has a mind of its own - Tracking feels effortlessly controlled

Tracking refers to the tendency to slide North-pegbox / South-tailpiece

Reliability of Play

Skating = 0 versus Secure = 10 - RH

Spitting feels like the bow can't produce an instantly reliable tone

Secure feels like the bow generates an instant effortless reliable tone - like touching silk

Stability of Tone - RH & LH

Wobbly = 0 versus Stable = 10

Stability of tone - the tone/pitch holds steady on bow strokes

String feels wobbly or indecisive under the finger on the fingerboard

Ease of Play at the Bridge - RH

Spitting = 0 versus Secure = 10

Ease of making a good sound when bowing Close to the Bridge

Playing in Tune - LH

Hunting = 0 versus Slotting = 10

Hunting feels like you have to discover or find the correct pitch

Slotting feels like the position of the pitch is so strong that the finger almost drops onto the correct pitch

Overglow - RH

Difficult = 0 versus Easy = 10

Overglow - the ease of making the sound to continue over into the next note creating a seamless gesture of notes.

Otherwise known as legato in music. Technically speaking the effect of overglow is also called elision as one tone elides to another in a very connected manner when/as desired by the player.

Speech - LH

Stutter = 0 versus Instant = 10

Stutter feels like the string takes its time to speak when changing from open to stopped string

Instant feels like the string speaks immediately when changing from open to stopped string

Stuttering is like letting the air out of a balloon, Instant is like popping a balloon

The violin must be checked for its response on jumping and bouncing strokes - how it maintains staccato, how it bites the string on spiccato, how it produces the sound from different parts of the bow.

Strong sensation of Pitch in the Sound - LH

Indefinite - 0 versus Definite = 10

Sound produces a strong Sensation of Pitch - makes playing in-tune easy

Focused or Centered tone - creates a solid core to the sound

We often use such words as "a juicy sound", "inner dimension of sound", "crystalline effect"

(which includes the idea of the inner space, like in the sound of crystal glass).

Distortion Resistance Effect - LH & RH

Distorts Easily = 0 versus Reserve = 10

Distortion Resistance - strings resist being distorted. Bowing the string is a form of distortion.

Ease of Producing Harmonics

Resiliency of tone - sound appears to bounce, when needed

Buoyancy of tone - a lightness of effect...the sound floats

Tonal Flexibility - LH & RH

Monochromatic = 0 versus Polychromatic = 10

Tonal flexibility imitates the expressive potential of the speaking human voice

Sound Color - conveys every timbre and affect intended by the player

Tonal Resilience - LH & RH

Lacking resilience = 0 versus Expressive resilience = 10

The ability to press deeply into the string without scratching but with expressive and even dramatic CHANGE of the tone similar to human sob or cry (to press and release the bow while moving along the string with real speed) The better violin is, the more expressive is this effect. The vertical movement of the string under different pressure of the bow contains special sound effects which can't be achieved by only horizontal movements.

Ease of Maneuvering about and holding the instrument LH & RH

Clumsy - 0 versus Easy and Deft = 10

The physical convenience of playing. It's about the construction of the neck, fingerboard, heel, nut and bridge.

The easiness of reaching high positions. Positiveness of Left hand Articulations.

The quality of flageolets and left hand pizzicato.

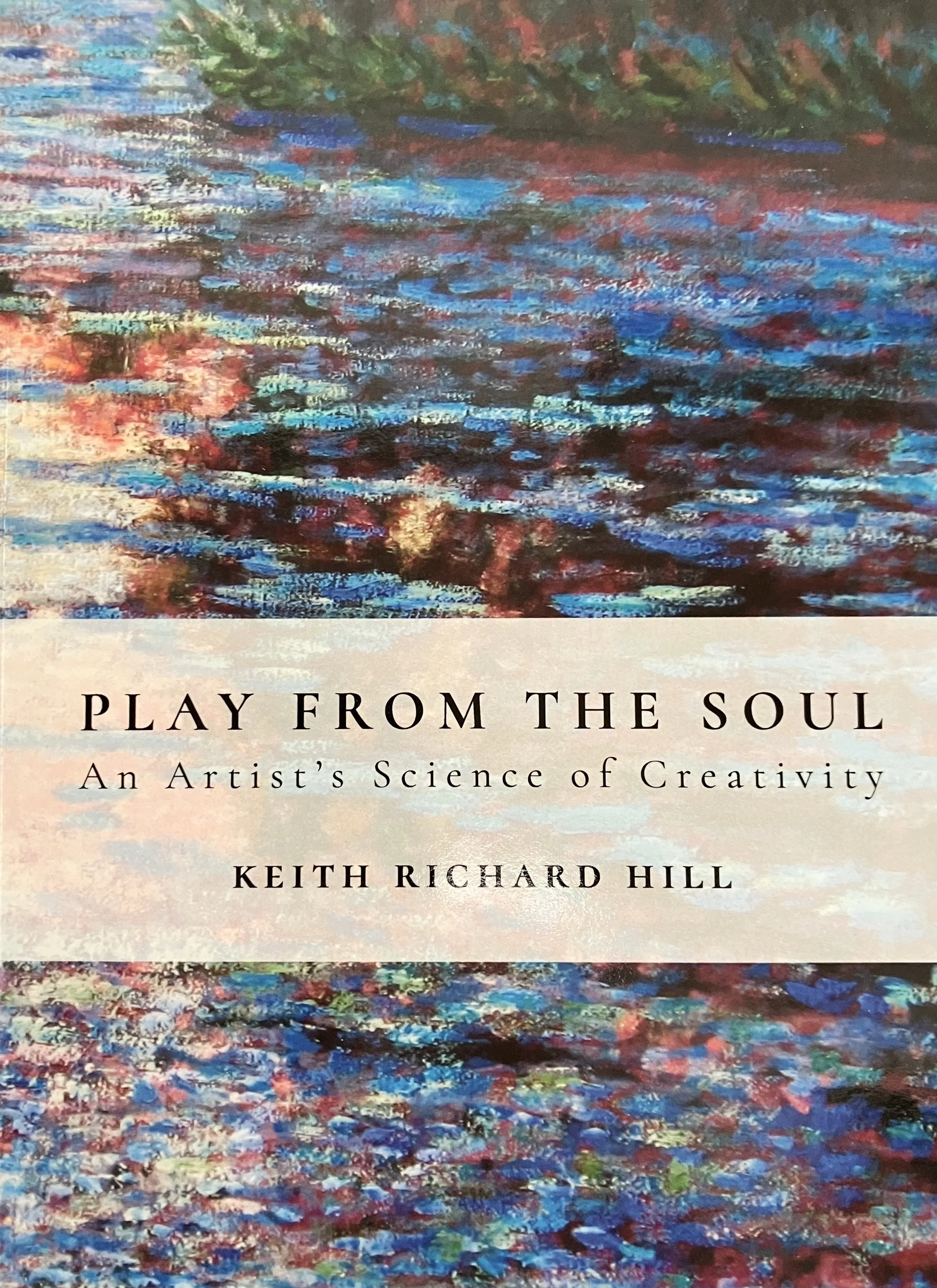

-Author of Play from the Soul -An Artist's Science for Mastering Creativity

Published May 2018.

The following is a review of Play from the Soul recently posted on the webpage on Amazon.

Keith Hill’s Play from the Soul stands in the spirit of the great aesthetic writings of the Renaissance through the lucidity and freshness of its thought. Where many contemporary books addressed to the creative being offer methods and prescriptions, Hill turns instead to something more fundamental: how to begin.

The effect is quietly immediate. As I read, I felt not persuaded but set into motion — not through mysticism, not through the comforting claim that everything already lies within, but through demonstration. Hill shows how the soul may be activated. The book opens a field of experience that had seemed inaccessible and makes it available to practice.

In Hill’s unfolding, C. P. E. Bach’s phrase “play from the soul” moves beyond musical advice and becomes a way of being. Playing becomes an orientation toward life itself: each gesture shaped by inner resonance rather than external demand, each experience deepened through the soul’s capacity to respond.

Play from the Soul does not remain at the level of aesthetic reflection. It enters practice — empirical, unpretentious, grounded in lived experience. Hill recalls art to clarity and craft, and shows how the creative process, when attuned to the music of the soul, acquires a coherence that is felt before it is understood. One senses in these pages the outline of a creative Renaissance — free of obscurity, unburdened by dogma, illuminated by awakened perception.

Mikhael Levy - Artist

Available on Amazon.com via the link below

https://www.amazon.com/dp/1986663892/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1525299377&sr=1-1&keywords=play+from+the+Soul

2013

- Has built 304 harpsichords, 32 fortepianos, 72 clavichords since 1972

2010

- Began writing: Play from the Soul

2008

- Began teaching Acoustical Technology to others.

2006

-Authored: Judging Violins - An article describing the 39 quality characteristics of great violins.

2005

- Acoustical restoration of an Italian harpsichord built by Hieronymous De Zentis of Viterbino in Rome in 1658

- Musical restoration of a 6 octave fortepiano by Conrad Graf, ca. 1815

- Ongoing research in painting and decorating techniques and media of the 17th and 18th centuries as well as from Egypt ca. 1500 BC and the 19th century Impressionists.

2004

- Conducted with Marianne Ploger a 3 day workshop on The Craft of Musical Communication at Weinberg Castle, near Linz, Austria

- Completed research on varnish making begun in 1980

- Exhibited paintings in one-man show at the Stove Factory Gallery in Charlestown, MA

- Exhibited paintings at the Chelsea Gallery in Chelsea, MI

2003

- Completed researches in Harpsichord acoustics begun in 1974

- Completed researches in Florentine Fortepiano acoustics begun in 1974

- Presented a lecture demonstration of The Craft of Musical Communication at Penny Farms Retirement Community, Penny Farms, FL

- Authored, Sensory Intelligence, a book which offers an alternative model for explaining human intelligence, based on a complex of over 134 senses divided between seven discreet faculties of mind.

2002

- Conducted workshops and lectured on The Craft of Musical Communication at Universities, Colleges, and Music Conservatories in the US and in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, France, and Sweden (University of Wisconsin at Stevens Point, Oberlin Conservatory, Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, Bremen, Linz, Berlin, University of Göteborg, Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen, etc.) and in Manchester, Michigan.

2001

- Co-authored, On Affect, with Marianne Ploger, an essay describing the structure of Affect in the music of great composers

- Co-authored, The Craft of Musical Communication, with Marianne Ploger, reworking an essay titled “Playing from the Soul, a new look at a familiar phrase” and developing the idea of the portamento techniques more completely.

- Presented ideas described and published in the article "Playing from the Soul, a New Look at a Familiar Phrase" in a Lecture/Demonstration, during a Seminar-- On The Musical Mind: Creativity and Models of Thought, at Hillsdale College, Hillsdale, Michigan, titled "Rediscovering the Lost Craft of Musical Communication".

2000

- Concluded research in Guitar acoustics

- Wrote Opinion Essay, published in the Guild of American Luthier's Journal #63

- Concluded acoustical research on Clavichords.

1999

- Concluded tanning experiments with a result of a 10 % improvement in resiliency over model samples taken from a Graf fortepiano.

- Concluded acoustical research in the area of Viennese Fortepiano making.

1997

- Presented "Playing from the Soul, a New Look at a Familiar Phrase” as a paper at the Midwestern Historical Keyboard Society in Beloit, Wisconsin including a demonstration on the harpsichord of the performance practice techniques outlined in the article.

- Began research into the acoustics of Guitars

- Participated as a presenter with Pamela Ruiter Feenstra and Marianne Ploger at the Improvisation Symposium sponsored by Eastern Michigan University

1996

- Wrote and published article on "Playing from the Soul, a New Look at a Familiar Phrase" at the request of the Japanese Clavichord Society for their Journal by that name

1995

- Began research into materials and materials processing relating to acoustics

- Began research into leather tanning to solve the problem of how to produce a vegetable tanned leather of deer skin suitable for fortepiano hammers using samples of leather from a Graf fortepiano 1825 supplied by the Academia Bartolomeo Cristofori in Florence, Italy.

1994

- Wrote: Treatise on the True Art of Making Musical Instruments, the Forgotten Craft of Enhancing Sound, 500 pages on the subject of practical acoustics for musical instrument makers with advice on how to think about the craft.

- Published article on Violin Varnish in the Guild of American Luthier's Journal #37

1993

- Authored a column in Continuo on improvisation called At the Moment

- Published article on quilling harpsichords, including a method for quilling using

- real bird feathers, titled Plastic versus Quill in the Continuo magazine.

- Taught a masterclass on improvisation at Ferris University in Yokohama, Japan

1992

- Began research into the painting techniques of 19th century French Impressionists

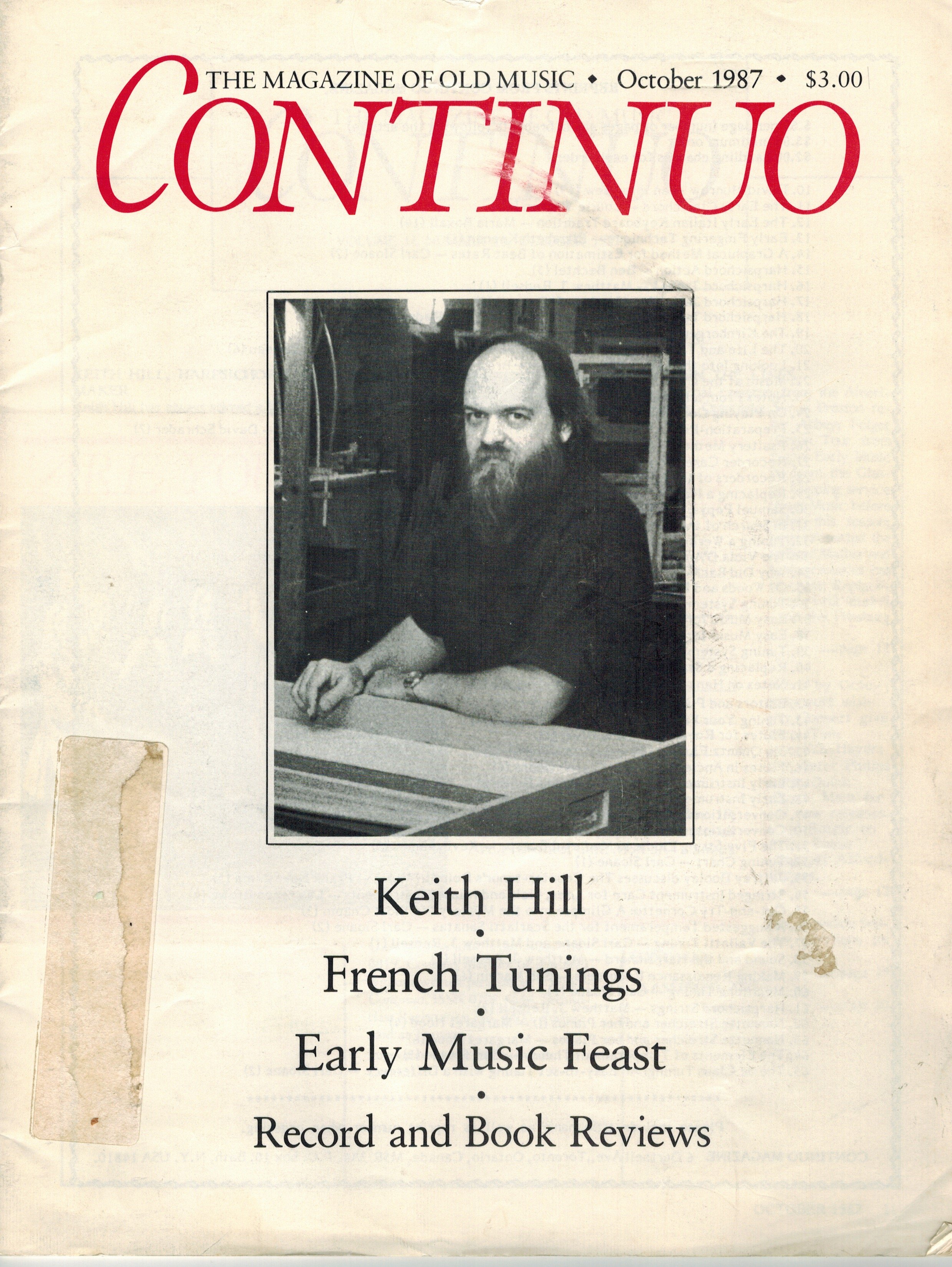

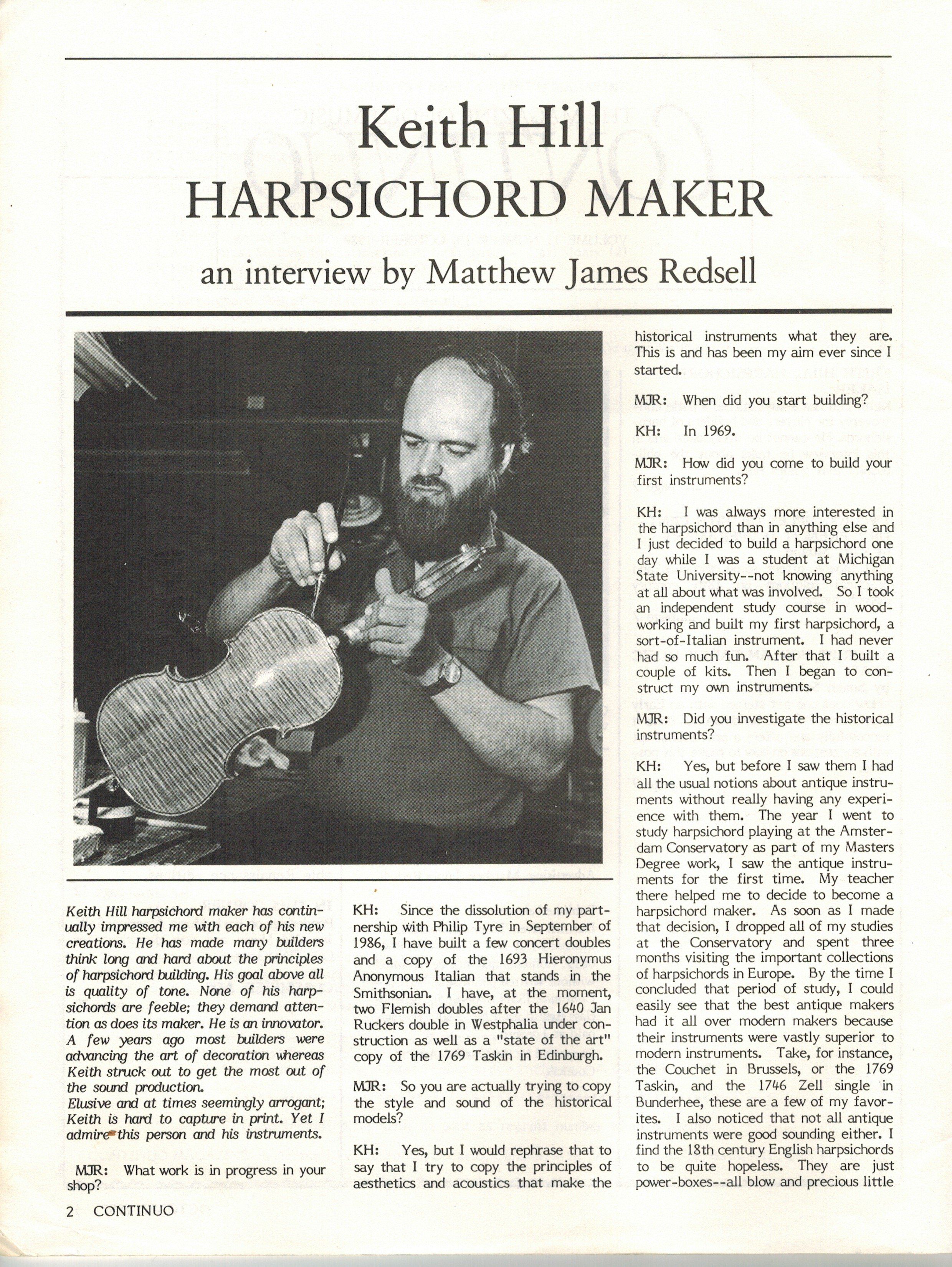

1987

- Featured Artist in Continuo, an early music magazine (October)

- Began research in the consequences of current improvisation methods. Developed a linguistic approach to improvisation called the Intentional Method of Improvisation.

1985

- Published article on How to Judge a Harpsichord in Continuo magazine

- Published article on The Anatomy of Authenticity in Continuo magazine

- Published article on Hints to Area Tuning the Violin in the Guild of American Luthier's Journal Vol. 1 # 1

1984

- Published article on Area Tuning the Violin in the Guild of America Luthier's Journal Data sheet # 283

- Developed a violin varnish, which reproduced all the observed characteristics, including the color of fluorescence under UV light, of the antique Italian violin varnish in use between 1550 and 1780, as recorded by authors on the subject of Violin Varnish from the earliest recorded observations to the most recent studies by Joseph Michelman. Conducted more than five hundred experiments in varnish making (preparing 58 separate formulas).

1980

- Began experiments in acoustic enhancement of violins, violas da gamba, double bass, and cellos.

- Began Violin Varnish making experiments.

- Began research into painting techniques and media of the 17th century Dutch and Flemish painters.

1979

- Invented a pedal harpsichord design which has since become the standard design used by other makers in the US for that type of instrument.

1978

- Discovered 25 Principles of Aesthetics which appear to govern the decision making processes of musical instrument makers, architectural designers, composers, painters, sculptors, decorators, writers, and performers from ca. 1460 to ca. 1870. These principles appear to be responsible for the exceedingly high quality of the average work done during that time.

- Developed an Aesthetic Philosophy using these principles as a basis. Used instrument making as an experimental venue for testing these theories.

1977

- Began research into decorating techniques of the 17th and 18th century European harpsichord decorators.

1972

- Began professional career as a Harpsichord maker in Grand Rapids, MI focusing specifically on the technology of acoustic enhancement as observed in the sound of the best antique harpsichords in playing condition found in American and European Collections

Output of Keith Hill -Luthier

Instruments with Opus Numbers as of February 8, 2026

385 Keyboard instruments

[72 Singles, 171 Doubles: French, Flemish, Hill, Italian, German, Austrian]

6 x 16’ Harpsichords

69 Clavichords

11 Pedal Harpsichords

1 Pedal Clavichord

1 Clavicytherium

1 Virginal

1 Cembalo Universale with 19 notes per octave

9 Lautenwerks

22 Spinets

19 Fortepianos

1 Three rank wooden organ

1 Modern piano soundboard for 1906 Grotrian Steinweg concert grand

1 3 Manual Harpsichord

8 Cellos

5 Double Basses/3 Violones

9 Violas

95 Violins

39 Violas da Gamba

2 Violas d’Amour

1 Psaltry

3 Rebecs

1 Fiedle (Vihuela)

3 Medieval harps

1 Irish harp (brass strung)

8 Guitars (2 Romantic, 1 Hill, 5 Torres)

1 Lute

Instruments having no Opus Numbers 90(+ - )

(experimental, given away, destroyed)

These instruments can be found in private homes, concert halls, churches, colleges, universities, schools of music, and conservatories in:

USA

Massachusetts

Arizona

Oregon

Colorado

Washington

New York

Washington D.C.

New Jersey

North Carolina

Pennsylvania

Florida

Maryland

Michigan

Virginia

Wisconsin

Vermont

New Mexico

California

South Carolina

Nebraska

Mississippi

Kansas

Tennessee

Indiana

Kentucky

Illinois

Ohio

Iowa

Texas

CANADA

Quebec

Ontario

British Columbia

EUROPE

England

Austria

Switzerland

Germany

France

Spain

Hungary

Italy

Norway

Denmark

Scotland

Netherlands

Finland

Poland

Sweden

Croatia

ASIA

Australia

Japan

China

Korea

PEOPLE WHO HAVE INFLUENCED ME AND MY WORK

This is a special Section on my website as it is about those people in my life who have influenced my thinking, attitudes and my work.

The first was Miss Mary Finn, my Latin teacher in high school. Because I apparently could achieve no better than a D in Latin, Miss Finn asked me why I bothered to take Latin when all it would do is drag down my grade point average. I told her that Latin was the only course I was taking that I thought was worth learning that year, so even if I didn't get a good grade in it I was still learning something relevant. From then on, she made sure I was always called on in class to recite part of the text we were translating, made sure that I earned my D, and took every opportunity to hold me after class to explain something that I wasn't understanding. She was a hard grader so I appreciated the course all the more because of the substance I was receiving. I credit my interest in words and the roots of words from that Latin class.

In college, I had the privilege of studying piano and carillon with Wendell Westcott, perhaps the world's foremost authority on Bells. Wendell could solve any problem involving the technique of playing the piano. He was far more musical than any of the other piano professors at the school and was interested in a large range of subjects, not just in piano. Wendell was the person in my life who taught me how to think and solve problems involving the mechanics of piano technique and the relationship between the shoulder, arm, wrist, hand, and fingers and the action of the piano. He saw virtually no problem that could not be solved by asking the simple questions:

What exactly is happening with ... ? followed by,

Assuming we are wrong, exactly what is happening?

Because I was armed with these two questions I have been able to solve almost every single acoustical problem I have faced.

In college I also had the benefit of studying piano tuning and technology with Owen Jorgensen, the famed author of the tome, Tuning the Historical Temperaments by Ear. Owen is the person I credit with my eventual decision to become a musical instrument maker because he recognized how easy it was for me to think about all aspects involved in matters historical as it related to musical instruments.

Once I began my career as a musical instrument maker, building an average of 8 double manual harpsichords a year, and began unraveling the mysteries that surround the subject of acoustics, I met Marianne Ploger, who introduced me to the real business of acoustical science, that is, the art of listening to exactly what was happening in a sound and understanding the business of hearing from a perceptual point of view. I immediately grasped the importance of Marianne's discoveries in the realm of basic acoustics when she shared with me her discovery of the phenomenon that people who possessed perfect pitch recognition were hearing that allowed them to know what pitch was sounding without any frame of reference. She reported that she could teach people to have perfect pitch recognition by showing them how to hear pitch in a special way. But it was after she asked for my assistance in explaining the phenomenon, that is, exactly what was happening that made it possible for people to recognize accurately any pitch they were hearing without a frame of reference, that I came to fully appreciate the enormity of the importance of her discovery. What she discovered was the single most important discovery in basic acoustics since Pythagoras worked out the musical ratios 2500 years ago. For anyone interested, visit her website at www.plogermethod.com to read about her work, methods and ideas.

The phenomenon she described to me in detail was clearly the keystone of musical instrument making because it was applicable to every aspect of constructing a violin, harpsichord or fortepiano, the instruments I have had an interest in since age 14. With that keystone it is possible to understand how the great musical instrument makers, like Stradivari, Guarneri, Ruckers, Schnitger, Taskin, Blanchet, Cristofori, Graf, to name a few, made decisions about how heavy or thick or thin or light to make a piece of wood to give it the desired sound quality. Furthermore, her discovery helped me to understand and explain the entire development of western musical tunings and temperaments and why some tunings and temperaments went out of fashion and why western music ended up with Equal Temperament with a standard of A-440. This discovery also explained how the circle of fifths really worked, tossing that concept into the realm of clear understanding of how musical pitch works. It also makes effortless an understanding of how the pre-20th century composers chose the key in which to write their music.

Where Pythagoras provided humanity with the "y-axis" in musical acoustics, Marianne Ploger had provided humanity with the "x-axis" in musical acoustics, the "z-axis" having been provided by all the greatest musical instrument makers in history. Every mystery, of which there are many in the realm of acoustics, is explainable using Marianne Ploger's discovery that she calls: Frequency Associated Timbre. Those mysteries are only disguised by the extreme subtlety of this phenomenon. Indeed, I spent a month with earplugs in my ears in order to prepare myself to be able to hear the phenomenon clearly when the earplugs finally came out. After I removed the earplugs I could easily hear the phenomenon and spent the following 2 weeks studying it in extreme detail in order to explain what was happening. Once I fully grasped the nature and importance of her discovery, all the mysteries surrounding the business of enhancing sound in musical instruments became exoteric, one after another, and so on in short order.

I could easily envision how her discovery could be applied to all manufacturing processes, to designing buildings, to human relationships, to resolving personality conflicts, to the design of every tool, implement, device and instrument, among other things.

For what Marianne discovered, she should be recognized world wide. But because we live in an age in which sound and music have been reduced to the crudest, rudest of terms in the general culture almost to the point of total irrelevance, her discovery has yet to be revealed to the general public. A truly spiritual person, Marianne avoids the spotlight to continue her investigations into sound and music. So it is no surprise that I say she is also an outstanding composer.

At her website www.plogermethod.com you can hear some of the pieces she has written and performed. In an age when beauty is scorned by so-called composers because they themselves can't produce it, and in which ugliness in all its tortured fowlness is extolled as a virtue because it provides an easy way to avoid feared comparisons to the great composers of the past, Marianne possesses no such fears and writes music to inspire the souls of listeners. She is a melodist in an age that scorns melody in music. She is an original contrapuntalist in an age in which composers are bereft the ability to write memorable music, not to speak of the ability to create counterpoint that is both original and meaningful. She is a harmonist in an age that trashes harmony in favor of dischord and cacophony.

And I have only touched on the surface of what other hidden phenomena she has uncovered. As a problem solver in the realm of music, musicianship, hearing, interpretation, and communication, Marianne Ploger has no equal. She has a cure for tone-deafness, poor sight reading skill, unmusical performing, and all manner of learning difficulties relating to sound and music. To say the least, Marianne is a wellspring of knowledge and solutions to every musical problem. So it is perhaps needless to say, I have learned more from her than any other single human being.

Finally, there are others who have influenced me and my work in less profound ways. Those who have taught me how to have the right attitude at the right time, who taught me how to see subtlety in varnished surfaces, who taught me the value of workmanship, who showed me the kindness of being extremely clear in criticism of my work, who provided me with assistance selflessly to further the quality of my work, and who have supported my work by wishing to own it and record music with my instruments. To those too many to name, I thank them.

REVIEWS OF KEITH'S

WORK AND IDEAS

BY THOSE WHO KNOW HIM PERSONALLY

A few years ago while writing a book, which I have titled: Play from the Soul -- An Artist's Science for Mastering Creativity, and intending to approach a publisher for the book, I asked a number of my friends if they would be willing to provide me with reviews of my work and ideas and was surprised by their willingness to write up a paragraph or two to submit to prospective publishers. I am still working on editing the book. In the meantime I have come to appreciate the degree to which what my friends wrote about me and my work and ideas provides as accurate a picture of me as is possible, and have decided to post those paragraphs here for those who might be interested to know something about what others think of me and my work. Curiously, I have never been particularly concerned what others may or may not think of me or my ideas and work, so it was an astonishment to me that they had so much positive to say. What follows are these paragraphs:

1

I have had the great fortune to work with Keith Hill over the past six years learning about the acoustical properties of wood, especially as applied to clarinet reeds. This work has covered the entire reed making process from the selection of tube cane to the most minute adjustments of the finished reeds. I have been a professional orchestral performer and university teacher for thirty-six years and thought I was quite competent with making reeds, but Keith’s teachings have totally transformed my entire reed making process. His process is thoroughly grounded in science, but also incorporates feeling and intuition, and is truly groundbreaking. I am confident that Keith Hill’s upcoming book will make a major contribution to human knowledge.

John Weigand

Clarinetist in the Baltimore Symphony

Prof. of Clarinet, University of West Virginia

2

When I first went to study with Keith Hill, I was expecting to learn some methodical acoustical recipes to improve my oboe reeds that he’d gleaned from decades making some of the world’s best harpsichords. Far beyond that, Keith taught me to listen to the reeds and make extraordinary demands of them in service to artistic ideals that transcend the oboe. He incorporated listening to recorded examples of awe-inspiring performances, detailed examinations of paintings, laws of the natural world, and a set of craft and affect principles that he developed in order to rekindle the imaginative and communicative power of music that has largely been lost due to a modern industrial approach used so much these days. His lessons continue to deeply inspire my performances and teaching at the University of Wisconsin and I believe his message needs to be heard now more than ever.

Aaron Hill

Prof. of Oboe

University of Arizona

3

During the last twelve years I’ve had the opportunity to deal with Keith’s concept of instrument making and with his musical philosophy as a whole. At first mainly through his essays; but Keith is always willing to share thoughts with interested musicians directly, and so we had a good amount of mail contact, and, when I visited him in Manchester, also a lot of inspiring talk – combined with some likewise inspiring, unconventional coaching at his harpsichords, exploring the meaning of “Musical Communication”.

Keith would never be content with just copying an antique instrument. He always tries to get into the “soulful intentions” of the antique instrument makers (be the instrument harpsichord, clavichord, fortepiano or violin) and to recreate an instrument in that spirit. “From the soul”, guided by the most important parameter: the absolute quality of sound. Keith gets every measure of an instrument from the exploration of sound in the material that he uses for his instruments, and he works with the material in a way that enhances sound. Therefore his instruments bear such a rich and generous sound character. And whenever I play a Hill harpsichord, I feel this character, and it touches and inspires me.

For Keith, the making of instruments has a spiritual sense. It’s not for itself. Instruments have to enable Musical Communication (as he and his wife Marianne Ploger have named and described it) and to tempt musicians to come to a real musical communication with their audience. That’s what his instruments- made “from the soul” - never fail to do.

Eckhart Kuper

Harpsichordist, Organist

Hannover, Germany

4

Keith Hill is a true living master of musical instrument building who has no modern equal in terms of excellence or approach. The book which Hill has written is an immeasurable resource for any person who hopes to achieve his level of fluency and expertise. His approach is completely unique. While other modern instrument builders base their building techniques on modern scientific means--physics, measurement, exact replication--Hill has gone against this grain and has rediscovered and further developed the ancient science of musical perception by being almost solely concerned with how the human mind perceives sound. The secrets of the ancient masters, people who created the world's masterpieces of sound without modern science, are alive again. In knowing Mr. Hill and his work, I would pay almost any price for a reference that would guide me toward his level of proficiency and help me to avoid even some of the pitfalls that are encountered on the path towards mastering any craft.

Matt Sullenbrand

5

For almost four decades Keith Hill has been making musical instruments, which draw forth the highest level of engagement both from performers and listeners. One does not acquire the skill to make such instruments in our times without an unflinching commitment to the quest to understand what is true and of lasting worth in the finest instruments of the past, to understand the nature of quality, and to commit all of one’s faculties – mental, physical, emotional – toward the realization of quality in one’s own work. If one considers the world of the harpsichord and clavichord, it is clear that no other builder in modern times has been so successful doing just this, in building such transcendently musical instruments. These are instruments which not only sound magnificent, but which also lead us to deeper experiences of the nature of music.

As a musician, I am helped, challenged, and sometimes brought up short by such instruments, an experience not unlike having a conversation with Keith himself. This is a rare treasure, to have such experiences. And such experiences eventually teach us that this kind of instrument is less of a tool for the performer than it is an entry point to an experience of transcendence.

It is not a foregone conclusion that there will always be people capable of making such instruments, and it would be tragic if this hard-won understanding and skill were to be lost to the future. Keith Hill’s book is for those who aspire to do likewise, as well as for all those who are drawn through love of such instruments to understand better their transcendent qualities. The publication of this work is an absolutely necessary step toward ensuring a healthy future for all the arts.

William Porter

Prof. of Organ and Harpsichord

Eastman School of Music

6

Keith Hill's instruments are not only beautiful to listen to, but also beautiful to behold. He has scrupulously adhered to principles for instrument making during the seventeenth and eighteen centuries, and extended his talents to include painting soundboard and case decorations based on period copies and ideals. His instruments are bold in sound, and stunning in their visual impact. As a player I experience expressive feedback through the sensitive touch of the keyboard and the aural behavior of the sound itself. This is not universally the case with many builders today.

Someone who accomplishes work at a high level necessarily has much to impart regarding core values in the workshop and the structural behavior of optimum sound. Philosophical statements and other information in various Baroque treatises have been an inspiration for his standards of workmanship.

Elizabeth Farr

Professor of Harpsichord and Organ

Director of the Early Music Ensemble

University of Colorado, Boulder

7

Keith Hill's approach to teaching is three-tiered: explanation and demonstration; guided hands-on work; and, repetition. Selflessly, he shares the knowledge he has gained through his own research, experimentation, and the observance and application of principles. He has published A Treatise on: The True Art of Making Musical Instruments, which discusses the acoustical enhancements that can be achieved through the understanding of pitch and tuning principles, and the implications to the action and instrument design. He has also published articles, available on his website, pertaining to various instrument making subjects. Two examples are “Plastic versus Organic” on the art of quilling, and “On Voicing and Regulating Harpsichords”. His experience, inquisitiveness, and his zealous pursuit of understanding and perfection make him truly a Master Teacher."

Mij Ploger - Harpsichord and Keyboard Maker

8

The attitudes and ideas that Keith Hill taught me over the years that I have known him have been invaluable to my development and work as a creative thinker. He offers an objective standard for art that I have not found anywhere else in the artistic world. Applying his method of building and maintaining a relationship with my soul has given me an edge on my competitors by creating a consistent flow of ideas and providing a way to identify ideas which are suitable to explore and develop. I have been able to integrate much of his work to the benefit of my everyday life, and I feel it is safe to say that if the artistic world were to put his theories into practice today, the result would be a artistic revolution.

James Raynor --screenwriter

9

Keith Hill has spent most of his life to rediscover the technology of making great sounding musical instruments made by the ancient makers of the past. The years of research have ended up in developing the acoustical technology with the help of which one is able to build various musical instruments using the same knowledge and applying it to any imaginable musical task such as making an instrument, designing a hall or playing a piece of music.

Not only has he discovered this extremely important knowledge, he has tested every idea on various musical instruments that he has built during his career. He has also proved that it is possible to transfer this knowledge to other people. I was trained by him over a relatively short period of time and am now able to reproduce his results in my own instruments. His book might be very important for anyone who is interested in the true principles on which real art is based.

Artiom Sinelnikov

Pianist, Violin Maker

10

Keith Hill is one of the most important aesthetic scientists in the world today. Mr. Hill is particularly adept at articulating the attitudes of history's finest artists and how they can be applied today. Keith keenly understands how materials can be most effectively used in creating aesthetic experiences for audiences.

Besides being one of the most important instrument builders since Stadivarius and Guarneri, Keith Hill is an accomplished improvisor, painter and teacher. Keith's approach is unique in that he is primarily concerned with timeless universal principles rather than today's subjective likes and dislikes. His delivery is honest, direct and humorous. I can hardly wait to read his book upon publication.

Dr. Charles Rochester Young

Assistant Dean

Conservatory of Music

Baldwin Wallace University

Berea, Ohio

11

"As I've begun to understand and apply the perspectives and acoustic principles Keith has revealed to me, my own approach to my work has been revolutionized.

At first, I didn't truly believe that the excellent qualities Keith envisioned for my results could actually be produced. Yet, I have produced results that surpass any other results produced by others today. Keith's perspectives have been truly transformational for my work.

I believe his book would help others who are receptive create truly great work in an era when this no longer seems possible."

William Stuart

Bagpiper and Reed Maker

Willimantic, CT

12

Keith Hill’s harpsichords, for their beautiful and complex sound, are one of the best physical demonstrations of the fact that together with scientific knowledge, a craftsman needs intuitive knowledge, just as much as he needs his right and left hand. Like the old alchemists he has found a way to transcend matter into a spiritual and aesthetic creation.

Rafael Marijuan

Harpsichord Maker in Spain

13

Like many musicians, I came to Keith Hill in search of a beautiful instrument with exquisite sound and complete responsiveness. But Mr. Hill hasn't always built instruments like this: he first needed to to find a new way of thinking, a process of continual invention and discovery that led him ever closer to his 18th century forbearers. The strength of this approach speaks for itself - it has led him not only to remarkable instruments, but also to vital, practical strategies for creating meaningful performances. There's no magic in this approach - just a set of principles, discoverable by others once they've learned how to look. This new book should help explain how Mr. Hill arrived at such a mindset. By inspiring and guiding others to do the same, this book may prove a valuable resource to succeeding generations of instrument makers, ensuring a future for the instruments and ideas that make expressive music-making possible.

Mark Edwards

Organist, Harpsichordist

Prof. of Harpsichord

Oberlin Conservatory

Oberlin College

Oberlin, Ohio

14

对凯特.山在乐器制作和音乐感知领域成就的评价:

作为一名在物理学和计算机科学等多项领域获得过学位的工程师,科技工作者,又从小就玩琴至今的音乐爱好者。我自信从原则上来说,我比绝大多数人,制琴师、音乐家或音乐爱好者,更懂得和了解被称之为<科学制琴>的方法,也就是用现代最先进的科学技术手段来制琴。我原来认为这方法可行。可是如此制成的琴声大都令我大失所望。琴声中仍然缺少一些东西,确切地说,就是缺少音乐元素。

多年来,我一直在乐器的制作过程中寻找音乐元素,未果。直到有一天我读到由凯特.山撰写的题为<提琴的分区调制>的文章。他在文中提出<谐律>是乐器制作的基本原理,并坚定地捍卫这一原则。谐,这是大自然的自然属性。多么精辟的原理论述!

无须多言,我们只需倾听他那根据这一原理制作的琴声,让我们的耳朵来引导我们加深对这一原理的理解。饱含<音乐>的琴声,胜过千言万语。

有些人可能会发现凯特.山制作的琴声与诸如阿玛蒂、斯特拉迪瓦里和瓜奈里还有许多其他制琴大师的琴声不完全一样。但在我看来,这正是原理的真正价值和力量所在:作为原理,它让我们可以根据各自对原理的理解和对音乐的感知来展望和实现自己的琴声;作为原理,它伴随着我们的艺术创作和总结。相比之下,如果斯特拉迪瓦里的琴声是阿玛蒂琴声的翻版,瓜奈里的琴声又是斯特拉迪瓦里琴声的翻版,如此等等,那将是多么的难以想象和令人不可承受。

虽然凯特.山在乐器制作和音乐感知领域的不懈努力和工作成果逐渐引起了人们的关注,但与其应有的地位还远不相称。对大自然原理如此深刻的思想内涵与理解值得在更广泛的同好间分享。

张平于法国巴黎

(As an engineer, a scientist graduated in physics and in computer science, and a music lover who plays the violin since childhood as I am. I believed that I was someone in principle better positioned than most people, luthiers, musicians or music lovers, in understanding the building of musical instruments in ways known as the “scientific approach” with the most modern, most advanced technologies possible. This is how I was convinced in the matter. But most of the time, the works made by this approach disappoint me. It still lacks some things, but I did not know exactly which.

For many years I failed in the search for musical elements during the construction phases of the instruments until the day when I read the first time the article by Keith Hill entitled "The Area Tuning the violin" in which he presents and defends the principle of harmony as the fundamental principle in the building of musical instruments. Harmony, existence in itself of the nature, what a wonderful principle! We need only listen the sounds from the instruments he built using exclusively this principle. Let our ears guide us in understanding the principle. A "musical" sound is worth a thousand words.

Some people may find the sounds of Keith’s instruments are not a carbon copy of the sounds made by instruments of the ancient masters such as Amati, Stradivari and Guarneri and many others. But I think that's where the real value of the principle settled: a principle that allows us to project and carry out our own musical sounds based on our understanding of the principle and our musical perception, a principle that accompanies us in our artistic creations and conclusions. In contrast, it would be unimaginable and awful that the Stradivari’s sound is the copy of that of the Amati and Guarneri’s sound is the copy of that of Stradivari, etc.

Although the works by Keith in his instrument making and his music perception begin to enter into the views of luthiers, musicians and all kinds of music lovers, but it's still not enough relative to its merits. Such a deep understanding of the nature deserves a sharing between those who enjoy.)

Ping Zhang - Engineer, Physicist - China - presently living in France.

15

I consider Keith Hill to be one of the most outstanding personalities I have met in my life. I have known him for a couple of years now. When I first contacted him it was in order to get a harpsichord made in his workshop. I had been looking for harpsichords for several years and though it would have been much easier and cheaper for me to order an instrument in Europe I found that his harpsichords are most inspiring and absolutely unique in touch and sound. Knowing what a harpsichord could be like I felt that everything else would be an unsatisfying compromise.

I soon discovered that being in touch with Keith Hill had to be more than a simple business relationship between customer and seller. His strong and rather unconventional way of thinking about how music ought to be played is controversial. For musicians who are open to his ideas they often work as a kind of release that sets free a lot of energy. As a musical coach Keith Hill is able to turn an average performance of any musical piece into a very musical, very speech-like and very intense personal interpretation within one single lesson.

As an owner and player of a very beautiful two-manual harpsichord made by Keith Hill, I have got a lot of positive feedback by harpsichord colleagues, other musicians and the audience. In my opinion there are very few harpsichords that can compete with his instruments except from the historic ones. Without copying historical instruments literally Keith Hill has succeeded in his art of making musical instruments to catch what I tend to call their spiritual quality. This is what makes his work so extraordinary.

Medea Bindewald

Harpsichordist

Mountsorrel

United Kingdom

16

Over the past decade, I’ve had the great fortune of knowing and working with Mr. Keith Hill. One of the fundamental things that I have learned from Mr. Hill is to make the time and effort to understand your passion from every aspect. Experience has taught me that while Mr. Hill makes very bold statements, every last one can be backed up as truth by the countless hours of observation, research and experimentation he spent on each one.

Leo R. Van Asten

Composer/Teacher

17

It is with great pleasure that I commend to you the work of Keith Hill, including the insightful writing he has generously made available over the years. Mr Hill's reach is broad but by no means superficial. His articles on such subject of the Craft of Musical Communication has long been a source of inspiration to me, and has had a powerful influence on my playing.

A particular strength of his writing is his use of common metaphors to render familiar concepts that might otherwise seem esoteric. He may even appeal to multiple senses to accomplish this: the effect of giving a deep hug in his idea on excrucis, for example. Mr Hill embodies the much sought after synthesis of artistry, intellect, and humanity.

Timothy Burris, PhD., Lautenist

18

More than any other instrument maker I know, Keith Hill has rediscovered the science of creating new work in old styles. I have known his work almost since the beginning, at a time when other instrument builders were making meticulous copies of antiques---a 20th century transitional approach. Keith, on the other hand, started by creating a vocabulary to describe sound, then began experimenting to understand how these various sonic characteristics were created and balanced in the old instruments. As the result of this process, a willingness to experiment outside of known models, and his extraordinary intuition, he has been at the forefront of instrument making in our time.

Roger W. Sherman

Organist, Harpsichordist, Recording Engineer,

Owner of Gothic Records

Orcas, WA

19

Keith Hill ranks among the most noted international keyboard and stringed instrument makers. After decades of intense research in ancient techniques, he now has compiled his findings in a book that communicates his process.

I find his book to be of unparalleled significance. It is a great pleasure for me to recommend this book for publication.

Wolfgang Rübsam

Professor Emeritus

Hochschule fur Musik - Saarbrucken, Germany

Church Music and Organ Performance

20

Keith Hill does not just think outside the box. He gleefully stomps on the box, flattens it and forms it into heretofore-unseen shapes. He steeps his mind in the rich stew of 18th century thought and emerges transformed by notions foreign to 21st century minds. This conceptual brew produces keyboard instruments that seduce the ear and delight the touch.

Hill pays profound attention to perception and bores down to an atomic level of indivisible essence, which he calls the universal principles. His thinking challenges, provokes, annoys and hones in on attitudes that produce excellence. These concepts will infect your thinking and attack your sense of self-satisfaction, but they may also goad you to the greatness you crave and fear.

Geoffrey Thomas

Budapest, Hungary

21

Keith Hill's remarkable insight, demonstrated in his writings, is the product of 40 years' thinking as an accomplished musician, luthier and painter. His writings on musical communication and the Principles that he espouses have significantly changed my thinking. I believe his proposed book would be essential reading for artists of any kind, historians, and the curious-minded.

Matthew Parkinson

22